- Home

- Archie Weller

Going Home

Going Home Read online

To Mum and Jack Davis—

both of whom encouraged my

writing in the difficult early years

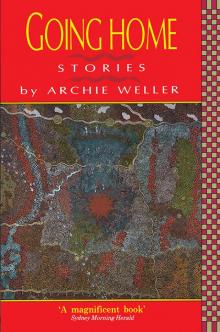

Cover painting: Warlugulong by Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, in part assisted by his brother Tim Lorra Tjapaltjarri,

Anmetjera Tribe,

Acrylic on canvas, 168.5 x 170.5

Aboriginal Arts Board, Australia Council 1981

Art Gallery of New South Wales

© Archie Weller 1986

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

First published in 1986

This edition published in 1990

Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest NSW 2065

Phone:(61 2) 8425 0100

Fax:(61 2) 9906 2218

Email:[email protected]

Web:www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Weller, Archie

Going Home

ISBN 978 0 04442 316 4

eISBN 978 1 95253 327 3

I. Title

A823.3

Set by Eurasia Press, Singapore

CONTENTS

GOING HOME

THE BOXER

JOHNNY BLUE

SATURDAY NIGHT AND SUNDAY MORNING

PENSION DAY

ONE HOT NIGHT

HERBIE

VIOLET CRUMBLE

FISH AND CHIPS

COOLEY

GLOSSARY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

‘GOING Home’ was first published in the Canberra Times; ‘Pension Day’ first appeared in Artlook magazine; ‘Fish & Chips’ first appeared in Paper Children from Darling Downs Press and ‘Herbie’ was first published in Simply Living 1984.

GOING HOME

I want to go home.

I want to go home.

Oh, Lord, I want to go home.

Charlie Pride moans from a cassette, and his voice slips out of the crack the window makes. Out into the world of magpies’ soothing carols, and parrots’ cheeky whistles, of descending darkness and spirits.

The man doesn’t know that world. His is the world of the sleek new Kingswood that speeds down the never-ending highway.

At last he can walk this earth with pride, as his ancestors did many years before him. He had his first exhibition of paintings a month ago. They sold well, and with the proceeds he bought the car.

The slender black hands swing the shiny black wheel around a comer. Blackness forms a unison of power.

For five years he has worked hard and saved and sacrificed. Now, on his twenty-first birthday, he is going home.

New car, new clothes, new life.

He plucks a cigarette from the packet beside him, and lights up.

His movements are elegant and delicate. His hair is well-groomed, and his clothes are clean.

Billy Woodward is coming home in all his might, in his shining armour.

Sixteen years old. Last year at school.

His little brother Carlton and his cousin Rennie Davis, down beside the river, on that last night before he went to the college in Perth, when all three had had a goodbye drink, with their girls beside them.

Frogs croaking into the silent hot air and some animal blundering in the bullrushes on the other side of the gentle river. Moonlight on the ruffled water. Nasal voices whispering and giggling. The clink of beer bottles.

That year at college, with all its schoolwork, and learning, and discipline, and uniformity, he stood out alone in the football carnival.

Black hands grab the ball. Black feet kick the ball. Black hopes go soaring with the ball to the pasty white sky.

No one can stop him now. He forgets about the river of his Dreaming and the people of his blood and the girl in his heart.

The year when he was eighteen, he was picked by a top city team as a rover. This was the year that he played for the state, where he was voted best and fairest on the field.

That was a year to remember.

He never went out to the park at Guildford, so he never saw his people: his dark, silent staring people, his rowdy, brawling, drunk people.

He was white now.

Once, in the middle of the night, one of his uncles had crept around to the house he rented and fallen asleep on the verandah. A dirty pitiful carcase, encased in a black greatcoat that had smelt of stale drink and lonely, violent places. A withered black hand had clutched an almost-empty metho bottle.

In the morning, Billy had shouted at the old man and pushed him down the steps, where he stumbled and fell without pride. The old man had limped out of the Creaking gate, not understanding.

The white neighbours, wakened by the noise, had peered out of their windows at the staggering old man stumbling down the street and the glowering youth muttering on the verandah. They had smirked in self-righteous knowledge.

Billy had moved on the next day.

William Jacob Woodward passed fifth year with flying colours. All the teachers were proud of him. He went to the West Australian Institute of Technology to further improve his painting, to gain fame that way as well.

He bought clean, bright clothes and cut off his long hair that all the camp girls had loved.

Billy Woodward was a handsome youth, with the features of his white grandfather and the quietness of his Aboriginal forebears. He stood tall and proud, with the sensitive lips of a dreamer and a faraway look in his serene amber eyes.

He went to the nightclubs regularly and lost his soul in the throbbing, writhing electrical music as the white tribe danced their corroboree to the good life.

He would sit alone at a darkened corner table, or with a painted-up white girl—but mostly alone. He would drink wine and look around the room at all the happy or desperate people.

He was walking home one night from a nightclub when a middle-aged Aboriginal woman stumbled out of a lane.

She grinned up at him like the Gorgon and her hands clutched at his body, like the lights from the nightclub.

‘Billy! Ya Billy Woodward, unna?’

‘Yes. What of it?’ he snapped.

‘Ya dunno me? I’m ya Auntie Rose, from down Koodup.’

She cackled then. Ugly, oh, so ugly. Yellow and red eyes and broken teeth and a long, crooked, white scar across her temple. Dirty grey hair all awry.

His people.

His eyes clouded over in revulsion. He shoved her away and walked off quickly.

He remembered her face for many days afterwards whenever he tried to paint a picture. He felt ashamed to be related to a thing like that. He was bitter that she was of his blood.

That was his life: painting pictures and playing football and pretending. But his people knew. They always knew.

In his latest game of football he had a young part-Aboriginal opponent who stared at him the whole game with large, scornful black eyes seeing right through him.

After the game, the boy’s family picked him up in an old battered station wagon.

Billy, surrounded by all his white friends, saw them from afar off. He saw the children kicking an old football about with yells and shouts of laughter and two lanky boys slumping against the door yarning to their hero, and a buxom gi

rl leaning out the window and an old couple in the back. The three boys, glancing up, spotted debonair Billy. Their smiles faded for an instant and they speared him with their proud black eyes.

So Billy was going home, because he had been reminded of home (with all its carefree joys) at that last match.

It is raining now. The shafts slant down from the sky, in the glare of the headlights. Night-time, when woodarchis come out to kill, leaving no tracks: as though they are cloud shadows passing over the sun.

Grotesque trees twist in the half-light. Black tortured figures, with shaggy heads and pleading arms. Ancestors crying for remembrance. Voices shriek or whisper in tired chants: tired from the countless warnings that have not been heeded.

They twirl around the man, like the lights of the city he knows. But he cannot understand these trees. They drag him onwards, even when he thinks of turning back and not going on to where he vowed he would never go again.

A shape, immovable and impassive as the tree it is under, steps into the road on the Koodup turnoff.

An Aboriginal man.

Billy slews to a halt, or he will run the man over.

Door opens.

Wind and rain and coloured man get in.

‘Ta, mate. It’s bloody cold ’ere,’ the coloured man grates, then stares quizically at Billy, with sharp black eyes. ‘Nyoongah, are ya, mate?’

‘Yes.’

The man sniffs noisily, and rubs a sleeve across his nose.

‘Well, I’m Darcy Goodrich, any rate, bud.’

He holds out a calloused hand. Yellow-brown, blunt scarred fingers, dirty nails. A lifetime of sorrow is held between the fingers.

Billy takes it limply.

‘I’m William Woodward.’

‘Yeah?’ Fathomless eyes scrutinise him again from behind the scraggly black hair that falls over his face.

‘Ya goin’ anywheres near Koodup, William?’

‘Yes.’

‘Goodoh. This is a nice car ya got ’ere. Ya must ’ave plen’y of boya, unna?’

Silence from Billy.

He would rather not have this cold, wet man beside him, reminding him. He keeps his amber eyes on the lines of the road as they flash under his wheels.

White ... white ... white ...

‘Ya got a smoke, William?’

‘Certainly. Help yourself.’

Black blunt fingers flick open his expensive cigarette case.

‘Ya want one too, koordah?’

‘Thanks.’

‘Ya wouldn’t be Teddy Woodward’s boy, would ya, William?’

‘Yes, that’s right. How are Mum and Dad—and everyone?’

Suddenly he has to know all about his family and become lost in their sea of brownness.

Darcy’s craggy face flickers at him in surprise, then turns, impassive again, to the rain-streaked window. He puffs on his cigarette quietly.

‘What, ya don’t know?’ he says softly. ‘Ya Dad was drinkin’ metho. ’E was blind drunk, an’ in the ’orrors, ya know? Well, this truck came out of nowhere when ’e was crossin’ the road on a night like this. Never seen ’im. Never stopped or nothin’. Ya brother Carl found ’im next day an’ there was nothin’ no one could do then. That was a couple of years back now.’

Billy would have been nineteen then, at the peak of his football triumph. On one of those bright white nights, when he had celebrated his victories with wine and white women, Billy’s father had been wiped off the face of his country—all alone.

He can remember his father as a small gentle man who was the best card cheat in the camp. He could make boats out of duck feathers and he and Carlton and Billy had had races by the muddy side of the waterhole, from where his people had come long ago, in the time of the beginning.

The lights of Koodup grin at him as he swings around a bend. Pinpricks of eyes, like a pack of foxes waiting for the blundering black rabbit.

‘Tell ya what, buddy. Stop off at the hotel an’ buy a carton of stubbies.’

‘All right, Darcy.’ Billy smiles and looks closely at the man for the first time. He desperately feels that he needs a friend as he goes back into the open mouth of his previous life. Darcy gives a gap-toothed grin.

‘Bet ya can’t wait to see ya people again.’

His people: ugly Auntie Rose, the metho-drinking Uncle, his dead forgotten father, his wild brother and cousin. Even this silent man. They are all his people.

He can never escape.

The car creeps in beside the red brick hotel.

The two Nyoongahs scurry through the rain and shadows and into the glare of the small hotel bar.

The barman is a long time coming, although the bar is almost empty. Just a few old cockies and young larrikins, right down the other end. Arrogant grey eyes stare at Billy. No feeling there at all.

‘A carton of stubbies, please.’

‘Only if you bastards drink it down at the camp. Constable told me you mob are drinking in town and just causing trouble.’

‘We’ll drink where we bloody like, thanks, mate.’

‘Will you, you cheeky bastard?’ The barman looks at Billy, in surprise. ‘Well then, you’re not gettin’ nothin’ from me. You can piss off, too, before I call the cops. They’ll cool you down, you smart black bastard.’

Something hits Billy deep inside with such force that it makes him want to clutch hold of the bar and spew up all his pride.

He is black and the barman is white, and nothing can ever change that.

All the time he had gulped in the wine and joy of the nightclubs and worn neat fashionable clothes and had white women admiring him, played the white man’s game with more skill than most of the wadgulas and painted his country in white man colours to be gabbled over by the wadgulas: all this time he has ignored his mumbling, stumbling tribe and thought he was someone better.

Yet when it comes down to it all, he is just a black man.

Darcy sidles up to the fuming barman.

‘’Scuse me, Mr ’Owett, but William ’ere just come ’ome, see,’ he whines like a beaten dog. ‘We will be drinkin’ in the camp, ya know.’

‘Just come home, eh? What was he inside for?’

Billy bites his reply back so it stays in his stomach, hard and hurtful as a gallstone.

‘Well all right, Darcy. I’ll forget about it this time. Just keep your friend out of my hair.’

Good dog, Darcy. Have a bone, Darcy. Or will a carton of stubbies do?

Out into the rain again.

They drive away and turn down a track about a kilometre out of town.

Darcy tears off a bottle top, handing the bottle to Billy. He grins.

‘Act stupid, buddy, an’ ya go a lo—ong way in this town.’

Billy takes a long draught of the bitter golden liquid. It pours down his throat and into his mind like a shaft of amber sunlight after a gale. He lets his anger subside.

‘What ya reckon, Darcy? I’m twenty-one today.’

Darcy thrusts out a hand, beaming.

‘Tw’n’y-bloody-one, eh? ’Ow’s it feel?”

‘No different from yesterday.’

Billy clasps the offered hand firmly.

They laugh and clink bottles together in a toast, just as they reach the camp.

Dark and wet, with a howling wind. Rain beating upon the shapeless humpies. Trees thrash around the circle of the clearing in a violent rhythm of sorrow and anger, like great monsters dancing around a carcase.

Darcy indicates a hut clinging to the edge of the clearing.

‘That’s where ya mum lives.’

A rickety shape of nailed-down tin and sheets of iron. Two oatbags, sewn together, form a door. Floundering in a sea of tins and rags and parts of toys or cars. Mud everywhere.

Billy pulls up as close to the door as he can get. He had forgotten what his house really looked like.

‘Come on, koordah. Come an’ see ya ole mum. Ya might be lucky, too, an’ catch ya brother.’

Billy can’

t say anything. He gets slowly out of the car while the dereliction looms up around him.

The rain pricks at him, feeling him over.

He is one of the brotherhood.

A mouth organ’s reedy notes slip in and out between the rain. It is at once a profoundly sorrowful yet carefree tune that goes on and on.

Billy’s fanfare home.

He follows Darcy, ducking under the bag door. He feels unsure and out of place and terribly alone.

There are six people: two old women, an ancient man, two youths and a young, shy, pregnant woman.

The youth nearest the door glances up with a blank yellowish face, suspicion embedded deep in his black eyes. His long black hair that falls over his shoulders in gentle curls is kept from his face by a red calico headband. Red for the desert sands whence his ancestors came, red for the blood spilt by his ancestors when the white tribe came. Red, the only bright thing in these drab surroundings.

The youth gives a faint smile at Darcy and the beer.

‘G’day, Darcy. Siddown ’ere. ’Oo ya mate is?’

‘’Oo’d ya think, Carl, ya dopy prick? ’E’s ya brother come ’ome.’

Carlton stares at Billy incredulously, then his smile widens a little and he stands up, extending a slim hand.

They shake hands and stare deep into each other’s faces, smiling. Brown-black and brown-yellow. They let their happiness soak silently into each other.

Then his cousin Rennie, also tall and slender like a young boomer, with bushy red-tinged hair and eager grey eyes, shakes hands. He introduces Billy to his young woman, Phyllis, and reminds him who old China Groves and Florrie Waters (his mother’s parents) are.

His mother sits silently at the scarred kitchen table. Her wrinkled brown face has been battered around, and one of her eyes is sightless. The other stares at her son with a bleak pride of her own.

From that womb I came, Billy thinks, like a flower from the ground or a fledgling from the nest. From out of the reserve I flew.

Where is beauty now?

He remembers his mother as a laughing brown woman, with long black hair in plaits, singing soft songs as she cleaned the house or cooked food. Now she is old and stupid in the mourning of her man.

‘So ya come back after all. Ya couldn’t come back for ya Dad’s funeral, but—unna? Ya too good for us mob, I s’pose,’ she whispers in a thin voice like the mouth organ before he even says hello, then turns her eyes back into her pain.

Going Home

Going Home