- Home

- Archie Weller

Going Home Page 2

Going Home Read online

Page 2

‘It’s my birthday, Mum. I wanted to see everybody. No one told me Dad was dead.’

Carlton looks up at Billy.

‘I make out ya twenty-one, Billy.’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, shit, we just gotta ’ave a party.’ Carlton half-smiles. ‘We gotta get more drink, but,’ he adds.

Carlton and Rennie drive off to town in Billy’s car. When they leave, Billy feels unsure and alone. His mother just stares at him. Phyllis keeps her eyes glued on the mound of her womb and the grandparents crow to Darcy, camp talk he cannot understand.

The cousins burst through the door with a carton that Carlton drops on the table, then he turns to his brother. His smooth face holds the look of a small child who is about to show his father something he has achieved. His dark lips twitch as they try to keep from smiling.

‘’Appy birthday, Billy, ya ole cunt,’ Carlton says, and produces a shining gold watch from the ragged pocket of his black jeans.

‘It even works, Billy,’ grins Rennie from beside his woman, so Darcy and China laugh.

The laughter swirls around the room like dead leaves from a tree.

They drink. They talk. Darcy goes home and the old people go to bed. His mother has not talked to Billy all night. In the morning he will buy her some pretty curtains for the windows and make a proper door and buy her the best dress in the shop.

They chew on the sweet cud of their past. The memories seep through Billy’s skin so he isn’t William Woodward the talented football player and artist, but Billy the wild, half-naked boy, with his shock of hair and carefree grin and a covey of girls fluttering around his honey body.

Here they are—all three together again, except now young Rennie is almost a father and Carlton has just come from three months’ jail. And Billy? He is nowhere.

At last, Carlton yawns and stretches.

‘I reckon I’ll ’it that bed.’ Punches his strong brother gently on the shoulder. ‘See ya t’morrow, Billy, ole kid.’ He smiles.

Billy camps beside the dying fire. He rolls himself into a bundle of ragged blankets on the floor and stares into the fire. In his mind he can hear his father droning away, telling legends that he half-remembered, and his mother softly singing hymns. Voices and memories and woodsmoke drift around him. He sleeps.

He wakes to the sound of magpies carolling in the still trees. Rolls up off the floor and rubs the sleep from his eyes. Gets up and stacks the blankets in a corner, then creeps out to the door.

Carlton’s eyes peep out from the blankets on his bed.

‘Where ya goin’?’ he whispers.

‘Just for a walk.’

‘Catch ya up, Billy,’ he smiles sleepily. With his headband off, his long hair falls every way.

Billy gives a salutation and ducks outside.

A watery sun struggles up over the hills and reflects in the orange puddles that dot the camp. Broken glass winks white, like the bones of dead animals. Several children play with a drum, rolling it at each other and trying to balance on it. Several young men stand around looking at Billy’s car. He nods at them and they nod back. Billy stumbles over to the ablution block: three bent and rusty showers and a toilet each for men and women. Names and slogans are scribbled on every available space. After washing away the staleness of the beer he heads for the waterhole, where memories of his father linger. He wants—a lot—to remember his father.

He squats there, watching the ripples the light rain makes on the serene green surface. The bird calls from the jumble of green-brown-black bush are sharp and clear, like the echoes of spirits calling to him.

He gets up and wanders back to the humpy. Smoke from fires wisps up into the grey sky.

Just as he slouches to the edge of the clearing, a police van noses its way through the mud and water and rubbish. A pale, hard, supercilious face peers out at him. The van stops.

‘Hey, you! Come here!’

The people at the fires watch, from the corner of their eyes, as he idles over.

‘That your car?’

Billy nods, staring at the heavy, blue-clothed sergeant. The driver growls, ‘What’s your name, and where’d you get the car?’

‘I just told you it’s my car. My name’s William Jacob Woodward, if it’s any business of yours,’ Billy flares.

The sergeant’s door opens with an ominous crack as he slowly gets out. He glances down at black Billy, who suddenly feels small and naked.

‘You any relation to Carlton?’

‘If you want to know—’

‘I want to know, you black prick. I want to know everything about you.’

‘Yeah, like where you were last night when the store was broken into, as soon as you come home causing trouble in the pub,’ the driver snarls.

‘I wasn’t causing trouble, and I wasn’t in any robbery. I like the way you come straight down here when there’s trouble—’

‘If you weren’t in the robbery, what’s this watch?’ the sergeant rumbles triumphantly, and he grabs hold of Billy’s hand that has marked so many beautiful marks and painted so many beautiful pictures for the wadgula people. He twists it up behind Billy’s back and slams him against the blank blue side of the van. The golden watch dangles between the pink fingers, mocking the stunned man.

‘Listen. I was here. You can ask my grandparents or Darcy Goodrich, even,’ he moans. But inside he knows it is no good.

‘Don’t give me that, Woodward. You bastards stick together like flies on a dunny wall,’ the driver sneers.

Nothing matters any more. Not the trees, flinging their scraggly arms wide in freedom. Not the peoople around their warm fires. Not the drizzle that drips down the back of his shirt onto his skin. Just this thickset, glowering man and the sleek oiled machine with POLICE stencilled on the sides neatly and indestructibly.

‘You mongrel black bastard, I’m going to make you—and your fucking brother—jump. You could have killed old Peters last night,’ the huge man hisses dangerously. Then the driver is beside him, glaring from behind his sunglasses.

‘You Woodwards are all the same, thieving boongs. If you think you’re such a fighter, beating up old men, you can have a go at the sarge here when we get back to the station.’

‘Let’s get the other one now, Morgan. Mrs Riley said there were two of them.’

He is shoved into the back, with a few jabs to hurry him on his way. Hunches miserably in the jolting iron belly as the van revs over to the humpy. Catches a glimpse of his new Kingswood standing in the filth. Darcy, a frightened Rennie and several others lean against it, watching with lifeless eyes. Billy returns their gaze with the look of a cornered dingo who does not understand how he was trapped yet who knows he is about to die. Catches a glimpse of his brother being pulled from the humpy, sad yet sullen, eyes downcast staring into the mud of his life—mud that no one can ever escape.

He is thrown into the back of the van.

The van starts up with a satisfied roar.

Carlton gives Billy a tired look as though he isn’t even there, then gives his strange, faint smile.

‘Welcome ’ome, brother,’ he mutters.

THE BOXER

THE scruffy tents were littered around the overgrown clearing; gaudy canvas facades. At night, the music blared and the coloured lights fluttered in the deep sky, enticing the townspeople to spend their money. As moths are attracted to a candle and burned to death, so ordinary people who hid from the harsh truths of life were shrivelled into nothing when they tried to penetrate the show people’s little world.

This was just a small sideshow company, travelling the circuit of hundreds of country towns; putting up for a night here, two nights there, taking in all the agricultural shows, and once a year the biggest of them all, the Royal Show in Perth.

There was a shooting gallery, a darts competition, a laughing clowns stand, a merry-go-round, drag cars—and the star turn of the small company, the boxers.

It was these three who kept the show going,

because there were always big country boys willing to win or have a go at winning the $40 offered for knocking out the champion and plenty of their friends willing to pay to see them try.

Young Jimmy Green was blonde haired and confident, with a cheeky smile playing over his smooth brown face and twinkling black eyes peeping from behind his tangled fringe. He was small and slight and seventeen.

Hector Nikel was slowing down and growing a bit fat. His black hair was going grey and his pugnacious face was wrinkling. Soon he would be finished as a boxer and would fade away. But right now, he still fought wildly, trying to stay on longer.

The last member of the troupe was the one who brought in all the money. He stood supreme and silent, staring out across the crowd, letting the waves of noise wash over him. He even had a show name.

‘Come up an’ fight Baby Clay... If you last three rounds, you can earn forty dollars! (Or $60 or $100—Mal varied the amount according to the size of the town.) ‘Come up and try yourself.’

Mally’s metallic voice would writhe among the crowd of spectators and the tentacles always dragged up a would-be champion.

The name had been Mally’s idea, too. The boxer’s proper name was Clayton Little, hence Baby Clay.

He would stand, confident in his prime, and wait.

From where he stood, on the shaky, creaky platform outside the tent, he could see the merry-go-round. He liked the merry-go-round, with its tinny music and happy children. It reminded him of life. The horses in a fixed unmoving stance, bright paint hiding the real ugliness underneath, glassy eyes staring ahead, going round and round, yet going nowhere. And always the laughter.

He had never had much reason to laugh as a child on the reserve, with his mostly-out-of-work father and his thin, dried-up, whining mother. Yet laughter had always been a part of their existence and, even now, a smile flitted across his squat, unreadable face as he remembered those early years.

The Littles had ten children. Clayton was the third eldest and the oldest boy, and, as such, the leader of the clan. Under his guidance they would wander through the town, gathering bottles and other discarded valuables. The town dump was a favourite source of supply. It was amazing what toys one could find in a rubbish dump. Once Clayton had found a twisted, tyreless bike, the victim of a smash. With the help of his two brothers he straightened it out and for months they used it to race, bumping down the bare brown hill, followed by the younger children in a hill trolley, also a product of the rubbish dump. Shrieking and laughing, they would all arrive at the bottom of the hill. Sometimes the trolley tipped over, spilling Littles all over the ground like a handful of grain. Then they would all trail up the hill for another go.

Sometimes Clayton and his young clan would press their faces flat against the glass of the town’s toyshop and their expressive dark eyes would light up at the glory they beheld. But they knew such treasure was not for them and agreed that the toys they made from scraps were more fun—and free.

As Clayton grew older, he and his friends would wander through the bush around the town. Swarming up tall trees, swinging from branch to branch like ragged little monkeys, playing in the sand quarry by leaping off the top into the soft sand six metres below. They all owned shanghais and were expert shots, taking home parrots, rabbits or wild ducks for the family meal around the open fire.

Jack Little did not believe in drink, and he made sure his family realised its danger, too. So Clayton wasn’t there when his two mates robbed the hotel and were caught. They were sent to a reform school to begin the long, cruel, well-worn and inevitable path that most of their people trod. Clayton was sad when Willie Cole and Harry Casey were sent away. He became restless and his mother feared he would do something to join them. So his father bought an old ute, and the family moved off; Jack sullen and grey-haired at the wheel, Reenie and the two babies beside him, and all the others stuck at odd points among the junky furniture piled in the back. The whole family left except Nancy, who was seventeen and intended marrying Wongi Cole when he came out of jail.

That was their style of life for the next few years. Rumbling along on the lumpy back of the rusted-red and white ute, a slow, cantankerous animal travelling the highways, being stared at by people passing, the people who were safe behind the shiny windows of their smooth new cars.

After grade seven, Clayton hadn’t had much education. It wasn’t his fault, nor his father’s; it was just life, having to move every six weeks or so. And, being the eldest son, he began work, helping his dad on the farms they stayed on. But he had learned to read, and enjoyed it.

‘Why does that boy waste ’is time readin’ them books?’ Reenie would want to know, and Jack would reply, ‘Aah leave him, honey. ’E’s real clever, Clayton. Pity ’e was bom a Nyoongah, but. Them wadgulas won’t give ’im a chance.’

The Little children enjoyed a carefree, easy life that seemed to consist mainly of playing and sleeping and playing again. At weekends the two younger brothers would help Clayton and his dad pick up roots or rocks, muster sheep, do fencing or any little odd jobs. But they still found time for fun. Out in the paddocks they were always surprising snakes, goannas or rabbits. Then Clayton would show off his prowess with a shanghai, and teach Arley and Lennard how to use it.

Sometimes at night Jack would take out the ute and hunt for a kangaroo or two. They would charge across rolling paddocks, the three older boys shouting with laughter and the sheer joy of living. Then Clayton would bring the bounding form skidding bloodily to earth. Lennard and Arley would leap out of the ute, often while it was still going, and dance around the dead kangaroo like bloodthirsty dogs. Jack would smile briefly, and pat Clayton’s thin shoulder.

‘Good shootin’, kid. You’ll git somewhere with that skill.’

His father rarely spoke and hardly ever smiled. But on nights like this he was once again a member of the Wile man people. He was hunting, as his ancestors had done before being shattered and scattered by the white man’s lust.

Sometimes he let Clayton drive the precious ute—precious because it was the only valuable item the Littles owned. It had cost all their savings and, more important, it was the only way Jack could move around getting work, so that he could keep his pride and not have to accept handouts and scorn—or pity, which is worse. Clayton understood this honour of being driver, and was proud of being a man in his father’s eyes. Although there were some nervous moments when he nearly crashed the ute, he soon became quite skilled. On these occasions the boys were treated to the sight of their father’s amazing shooting. He could put a bullet through the head of a leaping kangaroo from the back of the swaying ute almost every time.

Afterwards they would head back home with the loose, slack bodies bouncing in the back. They would skin them and keep what meat they wanted, then feed the rest to the pigs or dogs next day. The two younger boys would burst in, bright and bloody, to tell the family what they had done. Old Jack and thin Clayton would smile quietly and listen. Then perhaps Jack would play his guitar for them and sing before they went to bed.

So the Littles remained a happy, close-knit family. Clayton’s second eldest sister peeled off in Katanning and married Michael Hall. Then the family moved off again, leaving her behind.

But they were Aborigines, bound to find trouble sooner or later. Even if they didn’t look for it, they were the scapegoats of society, so the police pounced on Jack Little.

Clayton was seventeen then, tall and thin as a young tree being tossed in the winds of uncertainty. He was just reaching tender fingers out to feel life when the three policemen trod brutally upon them.

There had been signs of a thunderstorm. The heaviness of the air and laziness of the flies told the Aborigines this, while a dull grey curtain of cloud kept the sun and sky and spirits out.

Jack had parked the ute under some stringy white gums, their cool, smooth, white trunks marred by scars of grey, with bright green leaves offering shade to their dark, dusty brothers. Long strips of bark hung like tom dresse

s off the pale, virginal skin.

The youngsters were playing a game with the iron-brown pebbles by the side of the road, laughing and chattering. Arley and Lennard, both teenagers now—believing they were above the standard of baby games—played ‘stretch’ with an old vegetable knife. This was a game chiefly involving hurling a knife as close to your opponent’s foot as possible. Clayton and Jack were burrowing into the engine, fixing it up for the thousandth time. Old Jack might not have been well educated, but when it came to a car engine he could keep it going when most people would have put the wreck on the dump.

Suddenly, Reenie cried out anxiously, ‘Jack! Jack! Police comin’ here, look!’

The small man looked up uneasily and wiped his oily hands on his faded trousers.

‘What them bloody munadj want, well?’ he mouthed.

The sleek blue car pulled up with menacing slowness, and the only sound was the crunch of gravel. Then the three policemen got out and looked around. People going past on the highway stared scornfully out the window at yet another boong family being caught. Only once a carload of colourful surfies in a battered old Holden whistled, catcalled and shouted, ‘Leave ’em alone, you fuckin’ pigs!’

But the police had their victims now, so ignored them. The surfies probably forgot about the incident the next day, anyway. After all, it is common knowledge that if a darky’s not on the dole he’s in jail, isn’t he?

The three policemen circled the now silent camp, studying and looking. One, a thick-set, beefy sergeant with a broom-like black moustache, sauntered over to Jack and Clayton. He deliberately ignored them and looked into the engine.

‘Not much of a car we have here, is it? I hope you don’t expect to drive it on the road.’

‘’Ow else you reckon we goin’ to get to work? ’Ow you reckon we got ’ere, well?’ Clayton said before Jack could answer.

The policeman clicked his tongue and called over his shoulder, ‘We’ve got a right little bugger here, Joe. Got all the answers ready on his hot little lips.’

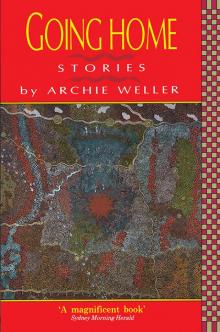

Going Home

Going Home